Greg Ross’s Apocalyptic Visions

After a decade working in streetwear, the LA–based designer steps out on his own.

What is taste and where does it come from?For designer Greg Ross, it may very well have been forged in the dusty aisles of the charity shops that line Main Street in Ventura, a shaggy surf town north of Los Angeles (Patagonia is based there). As a teenager growing up in the sun-bleached concrete sprawl of the city’s suburbs, Ross found himself at a lot of these types of stores; his mother, a schoolteacher, loved shopping for antiques, and she often brought Ross and his sister along. There, an hour or so up the 101, you wouldn’t find the curated elegance of high-end Hollywood vintage shops, or even the mundane treasures at thrift stores like Goodwill, but something shaggier, grubbier, zapped of any glamour or allure. Ross loved it.

“The clothes were inspiring to me,” the designer said during a call from his home in downtown LA, which also doubled as his studio. “I think it helped me figure out a style for myself, by looking at old clothes. They made me interested in fashion—I loved the textures, the colors. I loved wearing ripped things, I still do, I think because it was the opposite of what my mom wanted me to be wearing and the opposite of what the people around me were wearing. It opened the door to me liking clothing on a different level than just, you know, shopping for school clothes.”Ross, who is of Latino heritage, grew up in a mostly white world of skateboarders and surfers. In these time-faded, disintegrating garments, he saw a bit of himself—someone on the outside, but maybe proudly so. They helped him make sense of his place in these spaces. “It shaped a lot of my identity, because I was trying to constantly fit in with people that I didn’t look like. Clothes helped me feel comfortable with myself.”Ross came of age in the Tumblr era, and its flow of visual ephemera. It was also an exciting time of fashion and he discovered designers like Helmut Lang and Raf Simons, who shared with him a love of the subversive anti-luxury aesthetics, who took the frayed thrift store aesthetic that he was so drawn to and elevated it to the high-end catwalks of Paris and New York. It was at this time that Ross, who was considering a career as a fine artist, shifted his focus toward fashion design. Institutions like Parsons or Central Saint Martins seemed out of reach, physically, yes, but also financially, so he secretly enrolled himself at the local design college Otis, in Los Angeles, telling his mother only weeks before the semester started. There he learned the foundational skills of clothing design—sewing, patternmaking—but bristled against the assignments, like, say, making a Halloween-inspired vest in October (he stresses he deeply values his time at Otis despite these differences). While Ross would complete the assignments, he would do so through his own lens, creating garments that were oversized and distressed, each one connected to the last, building a collection. “It was kind of good for me, because I didn’t get to do what I wanted,” he said. “I tried to fit in my taste and ideas where I could.”

Ross eventually changed majors, at the advice of whimsical Dutch designer Walter Van Beirendonck, who was invited by the school to speak with students. Ross transferred to product design but still kept his eye on fashion, working on items like bags, shoes, and jewelry.His big break came during school, through his friend Elizabeth Hilfiger, daughter to Tommy, whom he met while interning at the LA-based label Libertine. (Ross applied for it on Craigslist, liked that the brand showed at New York Fashion Week, and recalls that administering copious amounts of crystals and fur onto garments was a key responsibility.) Hilfiger and Ross would work on extracurricular projects together at her house, where she had a studio, and one day her father swung by and offhandedly mentioned that he would be meeting with Kanye West later that night; Elizabeth interjected that Ross was a fan, and a few days later Tommy cold-called Ross and let him know that West would be in touch.“I was at home watching TV with my mom, and I said, ‘Mom, Elizabeth’s dad just called and said Kanye’s going to call me,’” he recalled. “She was like, ”Kanye called and spoke to Ross for an hour, about clothes and ideas he had, ending the conversation with an invitation to come to his studio for YEEZY, the apocalyptic streetwear brand that he designed for adidas.Thus began Ross’s decade-long involvement with the YEEZY brand. It was fate that Ross’s own taste—those hulking silhouettes, those washed-out earthy hues, those unraveling edges—overlapped with West’s own and that, thanks to Otis, he had the technical skills to help bring these quixotic ideas to life in the real world. Ross worked closely with the designer, in a fluid position. He has a book’s worth of fascinating stories: flying out to a small Texas town to have garments and accessories made at a factory that specialized in military clothing, later to be used in a fashion week presentation; being recruited to help West with his personal wardrobe; or being chosen to work in person with West during those strange early days of the pandemic, even traveling to Wyoming with him.

Ross keeps much of that time close to his chest, understandably so, especially considering his former employer’s fondness for tweeting without a filter. When Ross and I spoke last summer, he said he and West were still friends, and I got the sense he didn’t want to betray their relationship, both personal and professional. Still, when he recounted it, you could almost hear a certain awe creep into his voice. “Kanye taught me so many things,” he said. “So many people came in and out, but I was there pretty consistently because I understood him and what he liked. I think I was able to bring something to his equation. I wouldn’t be able to do [my own brand] now if I didn’t work there. He’s amazing at curating things, and figuring the collections out, and I learned that with him. He works with the best people you can get, huge people would show up every day, like [stylist] Lotta [Volkova], Carine Roitfeld. The best of the best for every aspect of making clothes.”But at a point over the pandemic, around 2021, Ross knew that if he wanted to do his own line—and he did, it had always been the goal—the time was coming. “It felt more realistic, and I was tired of waiting,” he said. So Ross got to work, designing his first collection under his own name. Instead of trying to create something distinctly different from YEEZY, he did the opposite, designing to show that, in some ways, he and YEEZY were inexorably linked. “I wanted to show people what I brought to the brand, how much of it was part of me.”

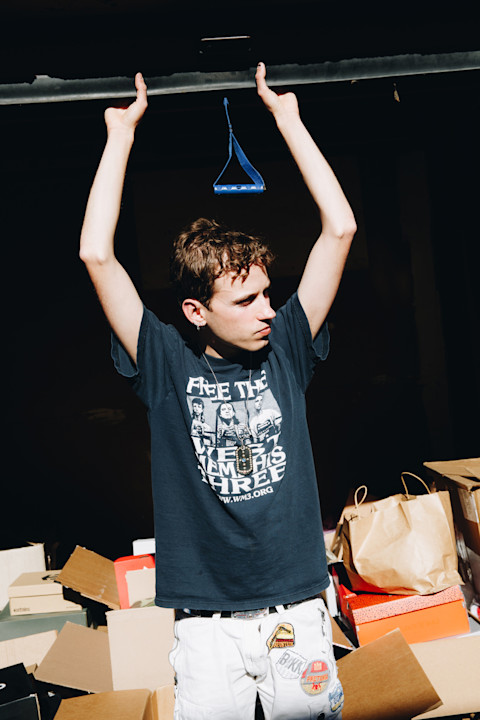

Ross keeps his output limited, and drops it in small batches. This is not a scarcity game, but a reality of being a small business in today’s economy. He is not yet big enough to be sucked into the whirl of the fashion calendar or the chains of wholesale delivery cadences, and, for now, seems uninterested in it. He is able, at his size, to deliver what he can when he can. “I’m OK, right now, at least, showing people one group of things at a time,” he said. “I have ideas all the time, I have enough for a few seasons, but what I can offer is a collection that has a lot of time and ideas put into it.” The clothes he creates aren’t about lofty ideas or heady themes. He’s not a conceptual designer; he’s a product designer, by trade, and a stylist. A pragmatist obsessed with, well, clothing, and how it looks and feels on the body.He often starts with a reference image or, more often, an item pulled from the racks of vintage he keeps in his studio. He’s often pulled toward hoodies and T-shirts because they’re familiar, and easily toyed with in terms of silhouette and fabrication.

Despite their familiarity, they come from a place of deep personal connection for Ross. “I think I always used hoodies and big clothes as a safety blanket to protect myself from what I thought people were thinking of me,” he said when I asked him about his penchant for oversized silhouettes. “And as I got older, it became a normal thing for me. And if I felt out of place, I wanted to dress how I felt: comfortable. If I have a big jacket on or a hoodie, I feel better.”Thus the oversize silhouettes or cocooning effects can lend his garments—so commonplace, so recognizable—a bit of theatricality. Some of his clothes, especially the ways they’re layered onto the body in his look books, can take on a sculptural appearance, or even a certain surreality. That’s, perhaps, my favorite aspect of them—that they’re so everyday, and yet also so alien and strange. It’s no wonder that Drake, Travis Scott, and Future have all worn his clothes onstage (and Kim Kardashian and Justin Bieber have been spotted in Greg Ross offstage).That balancing act—between extreme and everyday, between utility and unusual—is what gives Ross’s clothing its potency. Take, for instance, his current assortment, in part inspired by a moto jacket that he found on eBay and wore for the better part of 2022. That led to him making hoodies with beefy padded shoulders, and the collection, as it were, unfurled from there. “I was just taking normal things, normal shapes of things I wear every day, and exaggerating them,” he said. “But they’re familiar. There’s a sense of familiarity and comfort, but also an exaggeration of the shape—and I don’t think that will ever change. I’m never going to be Iris van Herpen, there will always be a realism and grounding to the clothes. I want people to wear these clothes and wear them for years.”

New York Times, GQ, Los Angeles Times,

Superfine: Met Gala 2025 It was a rainy night, but nothing could dampen the joyful atmosphere of the Met gala “red carpet,” which was blue and patterned with flowers for the evening. This year’s exhibition, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” explores the history of Black style and particularly Black dandyism based on the work of Barnard professor Monica L. Miller who collaborated on the show with Costume Institute curator Andrew Bolton.

Superfine: Met Gala 2025 It was a rainy night, but nothing could dampen the joyful atmosphere of the Met gala “red carpet,” which was blue and patterned with flowers for the evening. This year’s exhibition, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” explores the history of Black style and particularly Black dandyism based on the work of Barnard professor Monica L. Miller who collaborated on the show with Costume Institute curator Andrew Bolton.