JUN TAKAHASHI’S BATTLE WITH REALITY

The UNDERCOVER designer is at the peak of his powers. So why is he considering scaling back?

Backstage at UNDERCOVER’s show at Paris Fashion Week in June, the usual gaggle of journalists clamored in, brandishing dictaphones and mobile devices. Jun Takahashi had just shown his latest menswear collection to much applause, and the room was fizzing with excitement. The 54-year-old designer, laconic as usual, stood there alongside his translator in his signature dark shades and a wide-brimmed beige hat, not so much answering questions as fending them off.

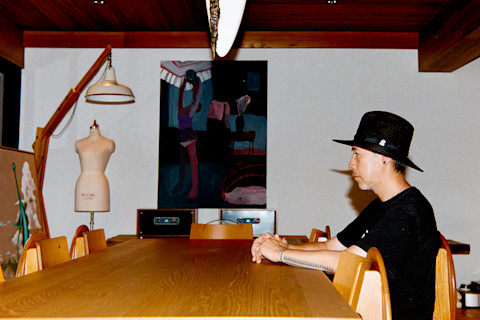

Takahashi is one of Japanese fashion’s biggest success stories. He has been called a sorcerer and an auteur, and is widely beloved in the industry for his showstopping runway spectaculars that mix all manner of subculture, film, and music references that spring forth from the toy box of his mind. His work can be wildly fantastical or punkishly practical. In 1998, he designed a collection called “EXCHANGE” that included garments with sections that could be unzipped from one garment and added to another. Last year, he showed a sheer golden coat, its back containing angel wings that looked as though they were trapped beneath the fabric. Currently at the height of his career, his place in fashion’s history books is already spoken for.When I meet Takahashi on a weekday summer morning at UNDERCOVER’s Tokyo HQ—an ultra-modern building in Harajuku designed to look like a shipping container—he’s wearing a faded black T-shirt printed with Picasso’s signature, and round, horn-rimmed spectacles that he puts on and takes off periodically. (Though later, when the cameraman arrives, he grabs his dark sunglasses and dons his hat by the Japanese milliner Kijima Takayuki.)Here, in the comfort of his own space, Takahashi appears much softer and friendlier than he was in Paris. His sprawling office, the inner sanctum of UNDERCOVER, takes up the entire top floor of the building. “It’s a mess,” he says. Takahashi is just being self-deprecating; what he describes as a mess is more a feast for the eyes. Bronze light fixtures by the designer William Guillon hang down from the ceiling like alien stalactites, and a shadowy painting by artist Robert Bosisio—whose abstract, atmospheric work Takahashi printed on his men’s collection this season—covers the far wall, while a ginormous replica of an ibis skull by Markus Akesson is placed in front, its beak curving high into the air. A war-wounded teddy bear missing half of its face sits nobly on a nearby table, the stuffing frothing out from its side—one of Takahashi’s own creations. The large boardroom-style table in the center, where we sit, is flanked with chairs that have an encircled A on their backs—for anarchy.

Perhaps the biggest thing in the office, however, is the pair of gigantic Altec speakers. Originally designed for use in movie theaters, they’re used by Takahashi for playing music when he’s in the office. (He also curates public playlists on Spotify; his latest features a spectrum of contemporary psych rock to a song called “Coffee Rumba” by Japanese legend Yōsui Inoue.) “I’ve been making one this morning,” he says brightly.Takahashi arrives at his office “usually about 10:30 or 11,” and clocks out around 6. “Then I go back home and walk my dog.” (His two-year-old Jack Russell, X, is sleeping soundly in the corner of his office.) On days that he’s not in Tokyo, he’s usually at his studio in Hayama, a well-heeled coastal town just over an hour south of Tokyo. He’s not a workaholic, then? “I used to be. But recently I decided a clear schedule, and when it’s finished I go home,” he says. “As much as I can, I try to keep work short. So after, I can turn my brain off and paint.”Takahashi’s paintings have been the source of much attention. Previously keeping his artwork to himself and his close circle as a private hobby, he debuted his paintings to the world last year, and held an exhibition in Tokyo where everything sold out almost immediately. Another will follow in Hong Kong this October. The paintings, which feature eyeless portraits and dreamscapes populated with otherworldly creatures, are a nod to surrealism, but Takahashi maintains that he relies on his own intuition for his work.

Just behind him, propped up against the office window, is one of his latest works: a huge canvas that is as epic in scale and narrative as Michelangelo’s . But instead of God and the first man touching hands, another scene unfolds: a large bluish humanoid figure, with an elongated neck and a tiny blank sphere for a head, is standing on the clouds, reaching out toward a wall-like rectangle filled with cartoonish demons. As they touch, a white bolt of electricity jolts through the center. In his recent men’s collection, the same image appears printed onto a blazer.Takahashi is reluctant to explain it. “It’s too difficult,” he shrugs. Oh, go on, I say. He laughs. “It’s about the wall and Pink Man, and they’re having a showdown,” he says. A Takahashi original, Pink Man—the bluish humanoid—is “kind of a devil or angel, or something like a machine.” The wall he’s squaring up against, which seems to be sucking him in, represents reality. “He’s fighting against it.” That battle is a familiar one for Takahashi. His oeuvre, and the alchemy behind it, has always been about a childlike rejection of reality, and the similarly childlike imagination that follows. This, above any fashion business nous or practical talent, is what has served him well. Where does it come from?Takahashi was born in Kiryu, a small city around two hours north of Tokyo. “It was a beautiful town, but it had a very dark atmosphere,” he remembers. “It was too hot in summer, too cold in winter, and there were no people. I felt like I was living only in my imagination.” When he misbehaved, his parents would lock him in the coal shed. He laughs about it now, but was that frightening darkness the source of his vivid dreams and nightmares? “Maybe, that’s just one element of it,” he says.

His parents often watched movies on the home TV. He remembers his father, who worked as the manager of an office cleaning company, pressing his slacks with an iron until they were pristine. “He wore these amazing flared pants,” he says. Later, in the upper grades of elementary school, Takahashi would marvel at the exuberant style of J-pop idol Masahiko Kondō. “I saw him wearing this complex silver blouson jacket and these Nike Cortez sneakers with black and silver lines, and I was shocked,” he says. “I had never seen silver clothes before; I thought he looked so cool.”Amidst the crowds of press, fans, and hangers-on backstage at his shows in Paris, an elderly Japanese couple can often be seen silently looking on. Takahashi is not especially close to his parents, but they have been a constant in his career. Though they still live in Kiryu, they always accompany him to his shows; in all the three decades that Takahashi has been putting on runway presentations, they have only ever missed one. “My parents don’t care about the theme of the clothes or the design, but they’ll tell me that I’ve worked hard, or that it’s amazing,” he says. “It’s a very pure thing.”It’s Takahashi’s way of connecting with them. “Japanese boys don’t talk so much with their parents. We’re not very open with each other. I think that’s a very sad thing and I don’t want to force that on my own children. I want to be as open as possible,” he says. “But, in a way, I’m exactly like my father.”At school, he gravitated toward the kids who also liked movies and music. “I wasn’t a badly behaved kid, but I got along with the bad kids,” he says. He enjoyed art, drawing, and social studies. He was terrible at math, and still is (his younger brother heads up the financial side of the UNDERCOVER business). After graduating high school he enrolled at Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo to study fashion. “I didn’t take school very seriously. I was always late, and I’d sleep through class because I was hungover. But even then,” he says, in comparison to his classmates, “I think my imagination was really different.”

Still, Takahashi was no layabout, and in 1993, together with Nigo—founder of BAPE and current designer at Kenzo—opened a Tokyo store called NOWHERE. The duo became a core part of the Ura-Harajuku (literally “backstreets of Harajuku”) streetwear scene. “Nigo and I were just having fun without thinking about anything at the time, but looking back on it, it seems like it’s become a big part of fashion history,” he says. He started out with silk-screen T-shirts, preempting the subsequent streetwear boom. “Designers like Virgil [Abloh] were definitely influenced by that,” he says. “I originally came from the streets, starting out in music and subculture alongside fashion. What I want to do is to mix those two things, put them on the same level and convey them to the world. My attitude towards creation is the same. Nothing’s really changed.”And yet everything has changed. In the decades since the Ura-Harajuku days, Takahashi has built one of Japan’s most famous fashion brands and today employs over 100 people, and you can buy his clothes anywhere from London to New York, Como to Chengdu. His themes, which he switches up each season, are eminently memorable and often cinematic. In recent years he’s printed Nosferatu silhouettes and Cindy Sherman photographs onto shirts; sent astronauts, Akira Kurosawa samurai, and droogs down his catwalk; and made masks and jackets inspired by the seminal ’90s anime .

Does he have a process for choosing his themes? “There is no special deep meaning. I decide each time based on the data I have in my mind and what I’m interested in at the moment,” he says. This season he found Glass Beams, an Australian band that he projected onto a screen at his Paris menswear show as they played their psychedelic, hypnotic rock music. He found them on YouTube after exploring the rabbit hole of the algorithm’s recommendations. “It knows my taste,” he laughs.Though his shows are celebrated, Takahashi is among a growing number of designers who finds the punishing demand of the fashion show cycle unsustainable; he is considering stepping back from showing womenswear to concentrate on his menswear, and dissolving the border between the two. “I think that the seasonal show system is questionable,” he says. “Raf Simons said online that doing collections several times a year is too much, and I agree with him. I wonder why people are happy about things like holding a fashion show and going viral. I think it would be better if they could make things with a little more substance.”For younger designers especially, he says, “It’s a struggle. The Japanese fashion industry can be very insular. If you start out as an independent designer, you have to go it alone. We don’t really have a system where someone will back you like they have in other countries. The industry needs a system where the government or companies come in to offer financial support.” His advice to the next generation? “To get serious, you have to show the world something that only you can do,” he says. “It’s easy to start, but it’s really hard work to keep going. Imagination is the key.”At the finale of UNDERCOVER’s womenswear SS24 runway, he unveiled light-up terrarium dresses, their glowing skirts filled with flowers and butterflies. It was one of the brightest highlights from his career, and captured the essence of what Takahashi does: something a little creepy, eerie, dark—but beautiful. The show was widely lauded, ranking just behind Prada on the Business of Fashion’s top ten shows of the season. “It was number two!” he says proudly. Still, he maintains he is not competitive. The nature of the fashion system doesn’t allow Takahashi to ride highs or lows for long. “Naturally I’m happy when something is well-received, and sad when it’s not well-received, but I’m not the type to dwell,” he says. “The next one is coming up, so I feel the pressure: What will I do next?”And what Takahashi do next? It’s a question that excites buyers, journalists, and fashion fans every season. Through canvas or clothing, he plans to continue reaching into the recesses of his mind to see what he can pluck out next, his raison d’être remaining resolute. “I originally came out of the street and started out in music and subculture—and what I want to do is to mix them on the same level.” So far, nobody has managed to do that quite like him. “I suppose there are very few people in my position,” he says. “But this is where I belong. This is my place in the world.”

The Wall Street Journal, Vogue Runway Vogue Business.

Basket Bags to Shop Basket bags are usually Recently a lot of luxury brands have launched basket bags as Loewe, Céline, Prada, and many more. Some people believe that basket bags are only dedicated to the beach, but I don’t agree, a basket bag can make an outfit look more summery and elevated. In this blog, we will see how we can wear basket bags in different ways, and we will discover as well several brands.

Basket Bags to Shop Basket bags are usually Recently a lot of luxury brands have launched basket bags as Loewe, Céline, Prada, and many more. Some people believe that basket bags are only dedicated to the beach, but I don’t agree, a basket bag can make an outfit look more summery and elevated. In this blog, we will see how we can wear basket bags in different ways, and we will discover as well several brands.