STAGE LEFT, RUNWAY RIGHT

Beyond balletcore, fashion’s vanguard continues to sing the body electric.

“You want a fashion show? It’s happening at 890 every day,” Melvin Lawovi purrs, name-checking in shorthand the address for American Ballet Theatre’s Manhattan headquarters.The spirited ABT dancer and I are discussing what it is about dancers’ innate style that makes them such enduring muses for fashion designers.

Few artists embody this dance-fashion fusion better than Lawovi. Raised in France by a seamstress mother and trained in fashion design at Parsons, he is a member of the corps at ABT as well as a choreographer of his own original works in which costumes are never an afterthought. “I feel like all my worlds are colliding,” he says.“Sometimes the choreographer comes in with nothing, not even a piece of music. It starts in silence. It’s just movement,” he explains. “It’s exactly like a fashion designer that starts, from nowhere, with a square of fabric. And then we craft something, and it’s [crafted] on us. It’s our bodies, but then they create something external.”Fellow ABT dancer—and subject—Kyra Coco underscores why this corporeal dimension captivates not just fashion designers, but also photographers and creative directors. “Dancers tend to know our bodies quite well. We stare into mirrors all day, 24-7, trying to achieve the perfect picture, essentially.”

For nearly two centuries, dance and fashion have performed an intricate . Designers have consistently referenced classical ballet and modern dance, two distinct movement traditions, when conceptualizing garments that blend structure with adaptability and precision with emotion.And now, a new generation of fashion creatives is drawing from movement and setting fresh sartorial choreography in motion.

The theatrical costumery of classical ballet permeated fashion in the twentieth-century through Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, the first dance company to collaborate with leading designers like Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel. Through the decades, ballet has been hard-coded into the DNA of fashion houses’ hero pieces, ultimately crystallizing into the trend dubbed “balletcore” in the early 2020s.“When balletcore first surfaced in the conversation, how it was executed was always so clean to me, which ballet is so not that. It’s blood, sweat, and tears,” says Dione Davis, a stylist and creative director, including experience as an apprentice with the Alabama Ballet, who credits her performing arts background with imbuing practical poise in her work for clients like Condé Nast and Proenza Schouler.Referencing a scene from Robert Altman’s ballet film , she notes how the apprentices were all sleeping on the floor of one squat: “I was like, Yeah, this is balletcore.”But prominent designers are increasingly introducing pieces that honor ballet’s juxtaposition of romantic narrative and physical complexity while also placing it in dialogue with other dance traditions.Simone Rocha’s collections plunge balletcore into something more labyrinthine by drawing on ceremonial rituals spanning Japanese butoh to Irish folk dance. “I like to look at traditional acts and see how they can be played out today and feel contemporary,” she says.Dance remains a touchstone for her because “it’s hardcore, the dedication dancers have, like athletes. It’s very inspiring as their creative expression and how they tell a story; it sets a scene. It feels quite close to fashion.”

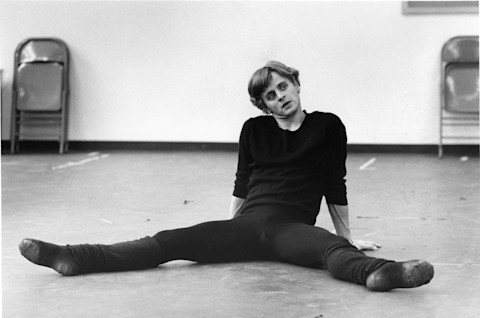

Partly inspired by iconoclast Rudolf Nureyev, whose outré performances throughout the 1960s and ’70s shattered conventions placed on the male ballet dancer, Ludovic de Saint Sernin’s Spring/Summer 2025 BDSM Ballet collection reimagines dancewear staples as vessels for carnal desire. “It was about taking the classical and making it feel almost illicit, blurring the line between elegance and eroticism, much like dance itself does,” the designer says.Lawovi appreciates that actual movement is informing designers’ approach, regardless of who the wearer is. “The grace is there,” the dancer says. “And I feel like designers pulling from that is really important, because they’ve finally realized, I just have to design for bodies, and not just for gender, which is what I love.”As a queer person, Lawovi longs for this fluidity to be commonplace: “I want it to be completely normal to see the male on stage with a skirt and not be like, ‘That was so good, so subversive.’ I’m just like, ‘He looked great, or they look great,’ whatever.”

Modern dance emerged as a rejection of classical ballet’s strictures on gender, physique, and codified movement, its unfettered expression resonating with like-minded fashion disruptors through the ages.In the early twentieth-century, Madeleine Vionnet, inspired by Isadora Duncan’s stagewear, pioneered the bias cut, emancipating women from onerous Belle Époque silhouettes. Later, Halston completed this artistic circuit by creating costumes for the Martha Graham Dance Company.Contemporary designers continue this interplay. Rui Zhou’s label RUIbuilt regularly adorns dance artists like Xie Xin in its webbed knitwear. “I personally have a deep appreciation for modern dance, which is why I wholeheartedly embrace such collaborative opportunities,” she says. “Even the movements of [our] presentation models are often influenced by contemporary choreography.”The alchemy of body, motion, and fabric intrigues sister designers Laura and Deanna Fanning, who head Kiko Kostadinov’s womenswear. Reflecting on their attraction to kinetic women—having previously referenced Vionnet and Sonia Delaunay, and most recently the enigmatic Australian dancer and bohemian Vali Myers—Deanna says, “Historically, the dance space was a world where women were allowed to work and flourish.” “And move!” Laura interjects.

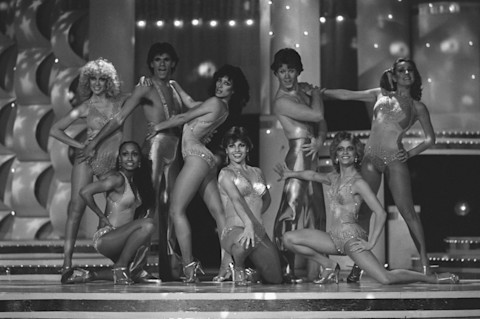

“Unlike [in] the West, where dress-up culture is often tied with fancy dinner events, dance culture has developed strongly within nightlife scenes in Korea,” explain fellow sister designers Boyoung and Jiyoung Kim of OPEN YY. “For many Korean women, these spaces provide important experiences for self-expression.” “If you think about it, a woman is essentially always on a stage,” says Laura. “People are always looking at her. They have something to say about what you’re wearing, how you look, how you do your hair.” “How you present yourself,” Deanna adds.Notably, hair and makeup design for the runway has taken cues from modern dance in interrogating artifice. Noting the “heavy Pina Bausch references” in recent presentations like Ferragamo’s latest, Davis observes that “there’s this raw beauty, everyone has long, flowing hair, barely any makeup, but there’s all so much elegance and glamour injected into it.” This influence builds on founder Salvatore Ferragamo’s legacy in the movement arts. “I always begin by spending time in the archives,” Maximilian Davis, the house’s creative director, reveals about his process for conceptualizing new collections, noting he “knew from the start” that dance would be center stage in both Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter 2025. “Salvatore was famous for making shoes for dancers, including Katherine Dunham, who was one of the first Black ballerinas,” he explains. “When I first saw this in the archives it opened a whole new world for me."

Fashion designers are increasingly looking to dancers’ lives outside the spotlight for fresh inspiration. “For SS 2025, I really wanted to explore that transition between rehearsal and performance, the in-between, half in costume—almost dress rehearsal,” Rocha explains. “The girls carrying their tutu to class, tucked under their arm, which then I translated into a bag, for example.”Dancers’ rehearsal styles are notorious for being wholly original (Debbie Allen! Gelsey Kirkland! Alvin Ailey!), blending function with personal expression.OPEN YY’s Kim sisters reveal that their Spring/Summer 2023 collection was inspired by a picture of “a ballerina throwing a coat over her shoulders as she heads home after rehearsal,” spawning brand mainstays like their bolero knit and rolled cargo pants, “inspired by dancers folding down the waistbands of their jersey pants during practice.”“How do I accentuate this versus that?” asks Chelsea Zalopany, stylist and HommeGirls market editor, imitating the dancer’s inner monologue. As an alum of the School of American Ballet, the official training ground for the New York City Ballet, she’s intimately familiar with the tactile handiwork required from both dancers and fashion creatives to achieve a desired illusion.“Wearing your skirt higher on your hips makes your legs look longer,” she says. “Or, especially with the feet, do you crisscross your ballet flats or do you do a single strap? It all comes down to, how can I look the best?”Arguably no contemporary line has centered the “dancer off-duty” aesthetic more than Live the Process, an activewear and lifestyle brand founded in 2013 by Robyn Berkley and Jared Vere that widened the aperture of performance apparel: insouciant elegance achieved through clean lines, high-quality fabrics, and versatile, layerable pieces. The brand’s foundational reference was a simple leotard, inspired by one Berkley lived in during a girlhood spent in dance class. (Live the Process’s leotards remain bestsellers.)“We are creating a feeling,” Berkley stresses, noting “everyone gets dressed” for the adult ballet classes offered at the brand’s Tribeca studio. When new exercise trends arise, Live the Process remains unwavering about its commitment to dance and similar modalities—“even when people are like, ‘Oh, hiking is interesting,’” she laughs.Zalopany, with her market expertise, expertly recalls fashion’s renditions on dancewear classics——LEMAIRE’s stirrup tights, Paloma Wool’s leg warmers—as well as some droller pieces. One such piece was worn by Mikhail Baryshnikov.

She remembers when “Misha” visited her class wearing lambs-wool warmup pants “reminiscent of a centaur straight out of A Midsummer Night’s Dream”—a look she observes later manifested in Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel collection for Fall/Winter 2010.

Will another dance boom emerge, reminiscent of the late ’60s to ’80s era when Baryshnikov graced Time covers and Tony Manero mimics took to mirrored dance halls to learn how to do the hustle?“You’ve got Jack Schlossberg taking adult ballet classes at the [ABT Jackie Kennedy Onassis School], and I love to see it,” Davis says. “All it takes is the right people tapping in, and also the right films,” she asserts, underscoring the importance of creating “new pathways” between dance and the zeitgeist. “I need A24 to do a rendition of Dancing on My Grave,” she says, referring to Gelsey Kirkland’s unnerving memoir about surviving the ’70s ballet world.Berkley posits another essential pathway: “Everything starts with music.”For future dance-inspired styles, Davis and Berkley predict Bob Fosse and will soon be ubiquitous. (Ready your Edward Cuming legwarmers and Coperni bodysuits now.)

Even as arts funding grows increasingly tenuous in nerve centers like the United States, Davis observes how fashion’s conoscenti remain committed patrons in their quest for visceral inspiration: “They all go to the ballet, they go to Ailey, they go to the opera, they go to the theater.”“Sometimes with fashion, it can be such a drainer. It can be a real drain when you think about the commerciality of it,” Laura says, chuckling. “And it’s just really important to understand that, actually, making fashion contribute to culture. In that way, it’s good to immerse yourself in many different types of performance, and that can feed back and help you.”“It’s also a pleasure to go to those things,” Deanna confirms. “We find joy in it.”“I’m ready for anything, because I love seeing what we do on a daily basis,” says Coco, who appreciates how fashion’s interpretations of her craft continue to expose dance beyond its traditional audiences. “It’s our own little world . . . I love seeing that come outside of just our studio.”