All in the Family: Why Heritage Logos Are Back After Having Never Left

Haley Mlotek On The Stories and Iconography Of Versace, Gucci, Burberry, Balenciaga, and More

1

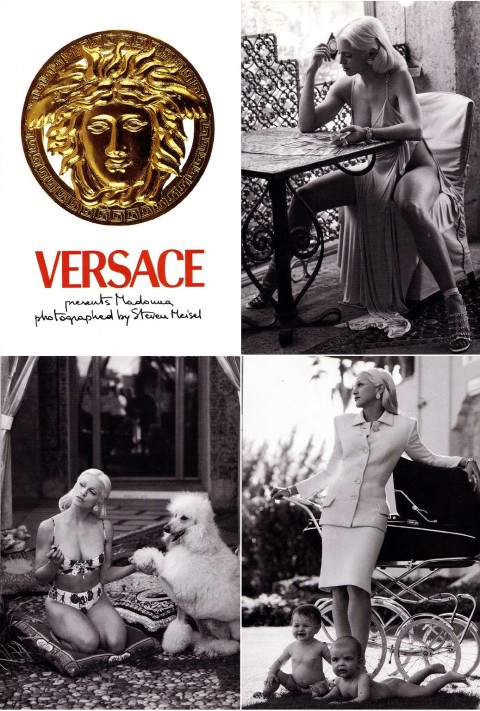

Giovanni Olandese grew up in Reggio Calabria, a city in southern Italy. He was a shoemaker by trade and an anarchist by heart, associating with many of the anti-fascist groups of the time. His daughter Franca was born in 1920, and as a teenager she wanted to be a doctor, but Giovanni’s progressive politics only went so far—he wouldn’t let her go to university. Instead she became a dressmaker, applying surgical precision to her tailoring. She could cut cloth without a pattern, just pins and her own intuition. Franca’s clothes had all the skill of the Parisian couturiers at half the price. She married a man named Antonio Versace, and they had four children: Fortunata, Santo, Gianni, and Donatella.In her excellent biography of the family, , Deborah Ball writes about how Reggio was a community known for Fascist sympathies, but Franca had inherited her father’s convictions, identifying as a socialist even though other women in her neighborhood rarely did the same. The Versace family liked to say their grandfather was so known for his political beliefs that anytime a leader of the Fascist Party from Rome would come to visit, the police would preemptively throw Giovanni in jail.As a teenager Gianni spent all his afternoons in his mother’s studio, begging her to teach him how to sew, and then making his baby sister Donatella into his muse, his mannequin, and one-woman focus group. They were partners in every respect, most obviously in how he made the clothes and she would wear them, but also in how she would steal their parents' car keys after they’d gone to sleep, and he would drive them to a nightclub to go dancing all night. Gianni moved to Milan in the 1970s, working as a designer for ready-to-wear knitwear companies and part of a generation who both inherited and instigated a profound social revolution: as Ball writes, in the first half of the decade there were more than four thousand acts of political violence before the assassination of Aldo Moro, the former prime minister, by a Marxist group called the Red Brigades. To wear couture or other symbols of old money at that time wasn’t just considered tasteless. It was fascist.The elements that we now recognize as being distinctly Versace came slowly over Gianni’s career, in stops and starts. Versace once said that when he was discouraged he would think of his mother and how she used to stay up all night just to finish a dress, and that would keep him going. His mother’s exacting standards weren’t just in his head. In the early days of the brand, she would sometimes drive down from Reggio before runway shows, and Gianni would find her backstage complaining that a hem was unfinished. By 1986, the house was pulling in about 220 million dollars in overall sales. The Versaces began investing in real estate in Milan, buying a three-story, 19,000-foot palazzo that had previously been owned by the Rizzoli family, who used to invite over other leftist intellectuals working during the post-war movement; the projection room in the basement had hosted one of the first screenings of Fellini’s .Elite Milanese neighbors apparently disapproved of the Versace family’s real estate holdings, and really disapproved of people they considered nouveau riche—rock stars, actresses—coming in and out of their neighborhood to visit. Gianni, a man with a sense for symbols, was too busy considering what the home meant to him to pay much attention to what other people thought. “On the knocker of its main double door,” Ball writes, “Gianni noticed an odd, if ominous, mythological figure: the head of a medusa, the legendary demon that turns any human being she lays eyes on to stone. He had been looking for a logo for his growing brand and found the medusa fitting, a reference to a childhood spent playing among the Greek relics in Calabria. The medusa was an apt symbol of the Versace brand’s sensibility, at once classical, alluring, theatrical, garish, and dangerous.” Though a door-knocker is supposed to invite visitors in, this one perhaps was intended as a challenge: who was brave enough to see the medusa’s strength and not her curse? That’s the woman Gianni wanted in his clothes.

2

Logos, whether made of symbols or letters, are complete texts. We learn how to read them. They’re often found in family lore and other forms of fiction. Some luxury brands have had centuries to accumulate meaning: Louis Vuitton, Hermès, and Cartier, for example, were all founded between the 18th and 19th century by skilled craftsmen who produced goods for royalty. Their logos are not like family crests—they are exactly that. In , journalist Dana Thomas writes of visiting the Louis Vuitton appointment-only luggage museum, The Museum of Travel, which is in the first Louis Vuitton factory in Asnières, a northeastern suburb of Paris. The “Damier” trunk, with its now-instantly recognizable brown and beige checkerboard pattern, was designed in 1888 by Louis Vuitton’s 31-year-old son Georges, and Thomas notes, “The words ‘Marque Louis Vuitton Deposée’—or 'registered trademark'—were written in white in a few of the checks, thus launching luxury branding.” Hallmarks and seals have been present since ancient times, as “marks of origin: you knew who made your goods.” Craftsmen in the Middle Ages were required to join professional guilds that certified authenticity and quality; it was the Industrial Revolution that took goods away from individuals and into assembly lines, and companies used logos in lieu of guilds but with the same purpose—to confirm and guarantee a consistent standard. “Since the 1950s,” Thomas writes, “trademarks and logos have been increasingly used as marketing and advertising tools and have evolved into brand symbols.”When considering clothes, couture, and other forms of commerce in the fashion industry, it is easy enough to say that questions of regional politics and social mores—to put it bluntly—don’t matter. Clothes are clothes, and politics are politics. To put it more delicately: there are two histories to the Versace family, one that concerns lineage and one that concerns fashion, and they don’t always intersect. But if we are to read and understand their logos, then both histories are of equal importance.“To me, you could throw the Versace medusa on a garbage bag and I would love it,” says Gabriel Held, a stylist and vintage dealer based in New York. Over email, we discussed his archive, where he tells me that everything with logo prints are by far the most requested items. As a stylist, he considers logos to be iconic and idiosyncratic; they are “as much of a classic pattern as stripes—the Dior trotter, the Fendi zucca—and monograms from Louis Vuitton and Gucci have been available for decades.” As a trend, “There was a time when logos were at the height of fashion, and then trickled down to streetwear,” Held says. “It’s less a question of specific time periods than it is about a specific type of dresser. There have always been devotees. I think that wearing logos when they’re out of favor is kind of subversive.”

34

Burberry, as a brand, has never been one for being possessive. The company finds value in its purpose, and luxury in usefulness. That’s not to say they don’t lay claim to their product. Far from it. Thomas Burberry was the inventor and patent-holder of gabardine, a crucial fabric with the most necessary properties for raincoats—weatherproof without suffocating the wearer. Their logo, the Equestrian Knight, carries a flag that says “Prorsum”—Latin for “forwards,” and Burberry as a brand has always aligned itself with the people they believe move in the same direction.The website proudly lists all the different ways Thomas’ invention came in handy, like in 1893, when Dr. Fritjof Nansen, a Norwegian polar explorer who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, wore it when he travelled to the Arctic Circle. The first person to fly between London and Manchester, aviator Claude Grahame-White, wore Burberry. Burberry made the uniforms for British Armed Forces in World War I and World War 2, developing and trademarking the Burberry check in the years between. The word “trench” came not from what it was—they were originally called the “Tielocken” coat, which admittedly doesn’t roll off the tongue in the same way—but from where it was worn. By the time the wars were won, the coat with the most distinctive name and lining was associated with the most loyal British citizens, whether soldiers or civilians. Until 1999 it was known as Burberry’s—as in, something belonging to Thomas Burberry, who was 21 years old when he founded the company in 1856.As the equestrian knight moved forwards, the look moved outwards. The Burberry check appeared in music videos, like in 2001, when Ja Rule wore a Burberry bucket hat in the video for “Always on Time.” In 2003, Beyoncé wore a Burberry bikini in the video for “Bonnie and Clyde,” with lyrics to match (“The only time she wear Burberry to swim,” Jay-Z rapped). In 2002, the British soap opera star Daniella Westbrook was photographed walking her daughter, both of them covered in Burberry check—Westbrook wore a purse and skirt in the pattern, and her daughter was wearing the same skirt, being lifted out of a stroller lined in Burberry check as well. cruelly wrote that it had the “lingering cloy of a half-sucked toffee,” and that it must be the end of Burberry now that it had been embraced by “nouveau rich naff.” The so-called “chavs”, working-class youth who also began to favor Burberry check at this time, were simultaneously derided for supposedly cheapening the brand, but their use of Burberry’s most immediately recognizable merchandise was part of the reason international licensing took off, leading to a massive increase in sales and popularity around the world.Connie Wang, senior features writer for Refinery29, points out that Burberry once worked to distance themselves from working-class customers, but that Christopher Bailey, who just presented his final Burberry collection during London Fashion Week Fall/Winter 2018, has done much to incorporate the status and reputation that comes specifically from streetwear. As such, today, the brand contains both meanings: “When you see that check worn with streetwear, it signifies a kind of high-is-low, up-is-down approach to 'class' and taste,” she explains. “But when you see it worn with conservative clothing, it still means that they have a very traditional conception of what good taste is.”Bailey’s final runway show featured the original Burberry logo—with the possessive “s” back where it was when Thomas Burberry founded it, when it was listed for the first time on the public stock exchange—this time in a rainbow print type face. Bailey told the collection was really about him, age 15, having his first profound reckoning with what fashion could do when he looked around the “DIY teen-tribe styles” hanging out in a basement club in Halifax, Yorkshire. Called “Time,” the last collection was about Burberry’s entire history, which includes Bailey’s 17-year career as creative director. The licensed merchandise, beloved and bought by the teens that Burberry had once tried to distance themselves from, were given their complete due under Bailey. A beige wool-check sweater scratches out the tartan print, as though to say “don’t take this too seriously,” while sweatshirts, bucket hats, silk scarves look exactly as they might have once in a duty-free shop, but now with the gravity of the runway. More than that, as Sarah Mower pointed out, Bailey has always made democracy the focus of his work at Burberry, and “that is surely why Bailey chose to wave farewell to Burberry in the way he did: with a collection full of symbolism of gay pride and with a large donation to youth charities that support LGBTQ+ rights and mental health.” This pointed and poignant finale, as Burberry announces that they’ve hired Riccardo Tisci as the new creative director, seems nothing less than Bailey reminding Burberry that they, too, must remember their own motto: they need to keep moving forwards.While logos stay constant, the trend known as “logomania” comes and goes like any other. There was the Lo Life Crew in the late 1980s, which was all about replicating the Ralph Lauren Polo Club lifestyle, wearing the brand in every way a brand could be worn—hats, sweaters, blazers, bags, if it had the logo it was on their bodies—and their interpretation of the designer’s specific ideas about the American dream became one of the most instantly recognizable trends of the decade, specific to New York and Brooklyn but understood everywhere.In 1982, Dapper Dan opened his Harlem storefront, renting from a furrier and slowly transitioning the shop into its own factory, with the staff sewing the clothes in the same building Dan sold them from, staying open twenty-four hours a day to keep his customers in his goods—fur coats and jackets and everything else covered in the logos of brands like Gucci, Fendi, and Louis Vuitton. Kelefa Sanneh wrote in a 2013 profile about how Dan used to go to Gucci stores and buy every garment bag they had, using them to make yokes and trims. Screenprinting allowed Dan to take the logos and blow them out of proportion: as Sanneh writes, “The Louis Vuitton logo pattern, which looked sensible on a valise, seemed surreal on a knee-length coat. For Dan, that was part of the excitement—he wanted to improve venerable brands by hijacking them.” He was sued multiple times by many of the brands he referenced in his work, among them a lawsuit from Fendi that happened to be assigned to Sonia Sotomayer, who was working for Fendi’s legal counsel at the time. The question was whether or not Dan’s work could be considered homage; goods are considered counterfeit and illegal when they are intentionally trying to mislead the customer, which was not what Dan offered. His clothing relied on brand recognition, of course, but it was never about replicating a straightforward brand loyalty.

5

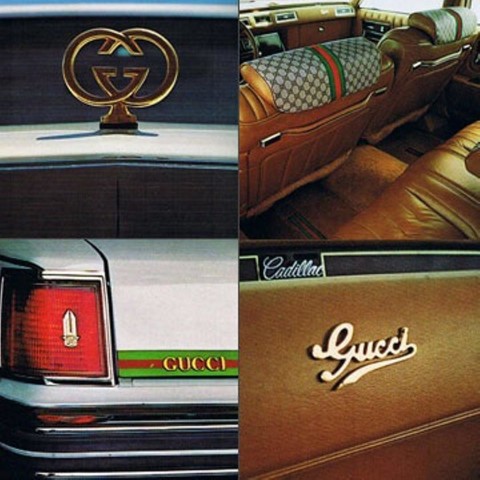

In 1897 Guccio Gucci was a porter at the Savoy Hotel in London, and in 1902 he returned to Florence to begin work with a leather manufacturer. In 1921 he opened his first stores, but the import embargoes of the 1930s meant he had to find his own alternative materials. The canapa he chose—a kind of hemp—was printed with tiny interwoven diamonds, dark brown on a tan background, and it’s been their signature ever since. In 1953, the Gucci loafer with horsebit was created; Aldo, his oldest son, opened the first American Gucci store in the Savoy Plaza Hotel in New York; and Guccio died 15 days later.Americans loved Gucci, and welcomed the brand into their most powerful houses—in 1961, the same year Jacqueline Kennedy becomes the First Lady, the company renames the Gucci purse she carries with her “the Jackie.” By 1985 the Gucci loafer was part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection. They added more and more signatures to their catalogue of prints and materials, like lush butterflies, tropical flowers, roaring tigers, bamboo and silk—the clothes and the accessories from Gucci have always evoked the sense of looking out a hotel window at the start of a vacation morning, expectant and contained.But the company and the family have had a volatile recent history. In 1995 Maurizio Gucci, one of Guccio’s grandchildren who had been appointed to the head of the house, was killed by a hitman hired by his ex-wife. Before the decade ended Bernard Arnault attempted a hostile takeover, lured by the rise of Tom Ford as creative director, who used the glossy provocations of tastefully sadistic sex in his clothing and, more importantly, his advertising (one of the most iconic images of that decade is the model with the Gucci “G” shaved into her pubic hair; another alternative material for branding, if you think about it) to great commercial and critical acclaim. Arnault wanted to make Gucci part of LVMH’s portfolio of brands, and after a bitter battle for control waged mostly through press conferences, the company was saved by Francois-Henri Pinault of PPR. That decade saw the rise of Tom Ford as creative director.In fact, an alternate history was almost possible—as Santo Versace was debating whether to take his family company public, he discussed an offer to merge Versace with Gucci, creating an Italian conglomerate that could hold its own against the ever-expanding roster of LVMH. The company was too similar in size, the family ultimately decided, and so Gucci became a part of PPR, now known as Kering, and Gucci is run by Alessandro Michele, who has embraced both the insider and outsider view of Gucci’s legacy.Rather than focus on the purely aristocratic clientele or the vicious battles for control, Michele’s line of vision stays up in the heavens, or the representations of them painted on the church ceilings that he loves so much. He’s held runway shows in Westminster Abbey, and his clothing frequently references the religious alongside the romantic to create what is becoming his distinctively twee Gothic interpretation of the Gucci brand, the sacred mixed with the satire.In 2012, the former Olympic snowboarder and current artist Trevor Andrew threw together a Halloween costume—a bedsheet with the Gucci “G” cut into it—the idea being that he was a “Gucci Ghost.” The name stuck, and so did the idea. His popular Instagram account showed him covering every surface he could find with his own version of the interlocking Gucci G’s, saying that he was going to keep doing it until Gucci sued him or hired him. Michele hired him to do a GucciGhost collaboration in 2016, which is still ongoing, like this Gucci backpack spray painted with the word “REAL” in dripping yellow letters.Most important of all, Michele has forged a working relationship with Dapper Dan himself, following an ill-advised attempt to incorporate a Dapper Dan design—a bomber jacket with balloon sleeves from the 1980s, it originally was made with the Louis Vuitton logo, but the shape and the concept of Michele’s version was otherwise virtually identical—into his collection without explicitly naming him or the original item. The critical response quite correctly pointed out that it was disingenuous for a company like Gucci, with its power and control, to take the transformative work of an independent artist without offering either credit or payment in return. Michele took the opportunity to reach out to Dan, and as of January their formal partnership is in business. No longer relying on garment bags, Dan now receives his materials directly from Gucci.The company has purchased a by-appointment-only storefront in Harlem, where Dan will continue to make his custom garments with complete creative control, and the support of the brand. This collaboration had a high-profile moment at the most recent Academy Awards, when Salma Hayek—who is married to Francois-Henri Pinault—attended the ceremony in a lavender Gucci gown, and wore a pink-and-gold two-piece Dapper Dan outfit to the afterparty, the Gucci diamond pattern made into the background for the “Dapper Dan” name spelled out in crystals between her shoulder blades. This is perhaps how Michele envisions the ongoing collaboration between the real thing and the imitators, collaborators, and artists working in the margins—he’s the real thing, and everyone else gets to join in the fun. His most recent runway show was inspired by Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto—her call for readers to think of themselves as being more than a human, and more, even, than a goddess, but as a hybrid capable of carrying many meanings and worthy of even more worship. As such, it’s only fitting that the holy trinity Michele worships is the father, the son, and the GucciGhost.

6

The logomania of the late 1990s and early 2000s was a constant presence in television shows like and , which dressed their sad and beautiful teenage girls in Burberry-checked handbands. Cameras followed them sloping through their high school hallways, flanked by lockers and a Chanel 2.55 purse casually slung over their arm. There was a certain amount of humor in this trend cycle, but the luxury branded items were treated very, very seriously: even if they were cute, even if they were easy, even if they were irreverent, they were always supposed to be real. The Prada backpack, made out of nylon parachute fabric and trimmed in leather was designed in 1984; instead of putting the initials of her company, like some fashion editors advised her, Miuccia chose to bring back the small triangle her grandfather had put on his luggage. At $450 it was the perfect price point for young women who wanted a piece of fashion’s prestige, and it became popular enough to factor into one of the best punchlines of the 1999 teen romantic comedy , when Bianca tells her friend Chastity that she’s learned the difference between like and love—she likes her Skechers, but she her Prada backpack.It was 2007 when Thomas wrote that “luxury brand items are collected like baseball cards, displayed like artwork, brandished like iconography,” saying that brands “have shifted the focus from what the product is to what it represents,” fulfilling the goal of a truly democratic luxury. There’s a tension, always, between what a brand wants their logo to mean, and the way a wearer can transform that meaning. “When luxury brands went democratic, they thought they could satisfy the middle market with lower-priced handbags and perfume,” Thomas explains. “What executives didn’t count on was middle-market consumers satisfying their craving for higher-end items by buying fake versions they could pass off as real.” The counterfeit purse trade blew up right alongside the trend for “it bags,” proving that the demand was there but that authenticity was not necessarily what customers wanted most. These were the years when Marc Jacobs worked with Stephen Sprouse to create a graffiti version of the brand’s monogram, and commissioned Takashi Murakami on a number of handbag designs including the cartoon cherry blossoms, a visual escalation from the existing naïf-style diamond, star, and flower pattern, which Georges Vuitton designed in 1896 as a protest against early Vuitton counterfeiters, registering a trademark for it in 1905. A century later these bags would become some of the most frequently knocked off purses, sold by counterfeiters and worn as easily as the real thing.Wang reminds me that “anytime youth culture, party culture, and excess are in—the late 1990s, the mid-2000s, and now—logos come back in trend. They become big whenever young people want to stunt in public.” To Wang, for example, the Versace logo speaks of a specific kind of Miami-Milanese “excess, hedonism, aggression. It says that you’ll be the first one to get weird at a party.” She points out that luxury logos printed on low-cost items is an accessible entry point to many brands, but that it also provides “an extra boost of relevancy via streetwear. There’s a level of irony in wearing a Balenciaga sweatshirt. It’s questioning what good taste is. If something has been traditionally in bad taste—velour sweatsuits or fanny packs, for instance—are given the luxury treatment, what happens then?” Then again, the instinct could be even simpler than that. “I think fashion people are always trying to horrify their parents,” says Wang.

7

Christobal Balenciaga was the son of a fisherman and a seamstress. He had a modest upbringing and an iron will. Recently, an exhibition at The Victoria & Albert Museum featured an x-ray of a 1955 silk taffeta dress so that visitors could see the skeleton of this piece of clothing, the infrastructure that held it together and let it be beautiful. When it comes to Balenciaga, it seems, it’s what’s on the inside that counts. One of the most skilled designers of his time and ours, he had no interest in the conventional establishment of the fashion industry. He refused to join the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, and he insisted on showing his collections a month after the Paris runway shows had ended—not unlike Demna Gvasalia, the current creative director of Balenciaga, who has moved his showings of Vetements between the different fashion weeks over the past few years, sometimes foregoing runway shows altogether in favor of a presentation.Today’s logomania makes brand recognition seem both rarified and ordinary, precious because it’s ubiquitous. It is meant to look as distinctive and be read as easily as a surname. To some, this version of the near-constant trend can be traced to Vetements’ Spring/Summer 2016 show, when Gvasalia sent fellow designer Gosha Rubchinskiy down the runway in a bright yellow t-shirt printed with the DHL logo. Here was a company with a singular, utilitarian purpose being elevated to high fashion just by association. When someone bought the shirt it was Vetements who got the cash, but when they wore it, DHL got the recognition. Even the CEO of DHL was photographed wearing one.The fashion industry is dependent on shipping companies like DHL; they pay huge sums of money for all kinds of deliveries, whether it’s getting samples from studios to runways, or relying on them to broker the import and export of materials and merchandise from factories to the shop floors. In many practical ways, DHL is as much a necessity to the fashion industry as the designer or creative director—what would happen to the clothes if not for the people in DHL uniforms making sure that they get past customs? DHL already works for a fashion brand like Vetements; why not, this t-shirt suggests, make their name work for Vetements. Gvasalia himself told that he made the DHL logo t-shirt because the company was so prevalent in his life. Every day there was another courier at his office he had to trust with his work, another package put in their hands.As critics have noted, as the creative director of Balenciaga, Gvasalia deliberately references prints from old licenses the house used to have for merchandise at duty-free shops—like Bailey at Burberry, he also has an eye on what were once low-cost status symbols sold as high-end souvenirs. Mower, writing for , reminds us that Gvasalia began his career at Maison Martin Margiela, and “his appropriation of ordinary things are fully in that tradition,” part of Gvasalia’s ongoing “corporate sub-theme.” The diagonal prints once seen only in the linings of vintage Balenciaga is now on the outside of sweaters, cardigans, heels, even sunglasses, for everyone to see, and the licensed merchandise that had the name of its founder but none of his ideas is made to be a true Balenciaga, name recognition secured and status restored. There is no nuance, no subtlety, with good reason: those are not qualities that Gvasalia admires.

In his time at Balenciaga, Gvasalia has also used the logos from brands like Champion, Juicy Couture, and in one memorable and easily-memed instance, he took the logo type from Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign and used it to spell out “Balenciaga.” “I don’t think the customer I like to dress cares about the deeper meaning behind the logos,” Gvasalia said in the same interview. “It is to create a visual suggestion linked to something corporate and formal without necessarily hiding a strong message or meaning behind it. It really is for the fashion insiders—for the people who know what’s happening behind the scenes, back in the kitchen.” For his second menswear collection at Balenciaga, Gvasalia showed a sweatshirt printed with the word “Kering,” the name of the conglomerate that counts Balenciaga along Gucci, Saint Laurent, and many other major luxury fashion houses in its holdings. “It’s pretty much just a reflection of my surroundings,” Gvasalia explained. Like Michele, his brother at work, he is attuned to dynamics of their patronage—where it’s housed, and who sits at the head of the table—but while Michele looks to the spiritual, Gvasalia evokes a kitchen, a domestic interior for a monolithic corporation.As Gvasalia reminds us of the original Balenciaga logo by putting what’s inside on the outside, he has a new contemporary version. In September 2017, the house unveiled a new logo they said was inspired by “the clarity of public transportation signage,” which seems like the punchline of a lightly surreal joke, one that levels and then collapses the history of families building trunks to pile onto cruise ships, duty-free shopping, the accelerated pace of a globalized fashion industry, the courier and the couturier on the same journey with the same destination with the same boss. The question of sons and fathers seems almost too small for a logomania this big. Why settle for making the bag, when you can be a brand as big as an airport? What does it mean to be a citizen, when the company you work for is practically as big as a country? Then again, the question might still be as simple as the one we started with: what’s a business without a family?

The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, n+1, and The Ringer,

Croatian Brutalism with Balenciaga, Martine Rose, and Gosha Rubchinskiy Danko & Ana Steiner Revisit Their Roots Plants exploit cracks and fissures in concrete in order to reach the fertile soils below, or the sunlight above. It all depends where the seed is sewn. In Zagreb, Croatia, a post-war communist Brutalist building complex features a utopic, elevated terrace. Pear trees, roses, apricots and daisies flourish against the stark concrete surrounding them. For his latest SSENSE editorial, Danko Steiner returns to his roots in this Croatian city. With Martine Rose , Balenciaga and Gosha Rubchinskiy , Danko and Ana Steiner pay homage to their 90s adolescence—calling on the aesthetics so reminiscent of the era in which they began to thrive.

Croatian Brutalism with Balenciaga, Martine Rose, and Gosha Rubchinskiy Danko & Ana Steiner Revisit Their Roots Plants exploit cracks and fissures in concrete in order to reach the fertile soils below, or the sunlight above. It all depends where the seed is sewn. In Zagreb, Croatia, a post-war communist Brutalist building complex features a utopic, elevated terrace. Pear trees, roses, apricots and daisies flourish against the stark concrete surrounding them. For his latest SSENSE editorial, Danko Steiner returns to his roots in this Croatian city. With Martine Rose , Balenciaga and Gosha Rubchinskiy , Danko and Ana Steiner pay homage to their 90s adolescence—calling on the aesthetics so reminiscent of the era in which they began to thrive.  How Tattooing Has Become an Aesthetic Power Source in Fashion Sang Bleu Founder Maxime Büchi Speaks Out on Tattooing’s Role as a Subcultural Lingua Franca Maxime Büchi is the man who made sense of tattooing’s contemporary relevance. Arriving in mid-2000s East London as a graphic designer with a love of fashion and publishing, he discovered a world where diverse subcultures and creative disciplines could overlap in a cohesive way. Tattoos were the common thread tying these radical groups together—an underground cabal that powered the grittier side of design, and an antidote to fast fashion’s throwaway ethics.

How Tattooing Has Become an Aesthetic Power Source in Fashion Sang Bleu Founder Maxime Büchi Speaks Out on Tattooing’s Role as a Subcultural Lingua Franca Maxime Büchi is the man who made sense of tattooing’s contemporary relevance. Arriving in mid-2000s East London as a graphic designer with a love of fashion and publishing, he discovered a world where diverse subcultures and creative disciplines could overlap in a cohesive way. Tattoos were the common thread tying these radical groups together—an underground cabal that powered the grittier side of design, and an antidote to fast fashion’s throwaway ethics.  Salomon and the Rise of Hyper-Functional Fashion Writer Gary Warnett Delivers a Closer Look at the Brand Creating Today’s Most Trend-Setting Sneakers Where do we go when every single interesting archive oddity has been reissued, referenced ad nauseum, or spliced clumsily with modern technology? We head upwards.

Salomon and the Rise of Hyper-Functional Fashion Writer Gary Warnett Delivers a Closer Look at the Brand Creating Today’s Most Trend-Setting Sneakers Where do we go when every single interesting archive oddity has been reissued, referenced ad nauseum, or spliced clumsily with modern technology? We head upwards.